By Sarah Glassford

Posted September 9, 2022

For anyone born over the past 70 years, Queen Elizabeth II (1926-2022) has been a rare point of stability in a fast-changing world. Her death on September 8th could not be called shocking (given her age and the gentle warning given to the public earlier in the day that she was under medical care), but for many people it nonetheless feels jarring. Whether you are a monarchist or republican, a royal-watcher or unconcerned with royal affairs, the death of Elizabeth II – Queen of Canada, Britain, and other nations of the Commonwealth since 1952 – marks the end of an era.

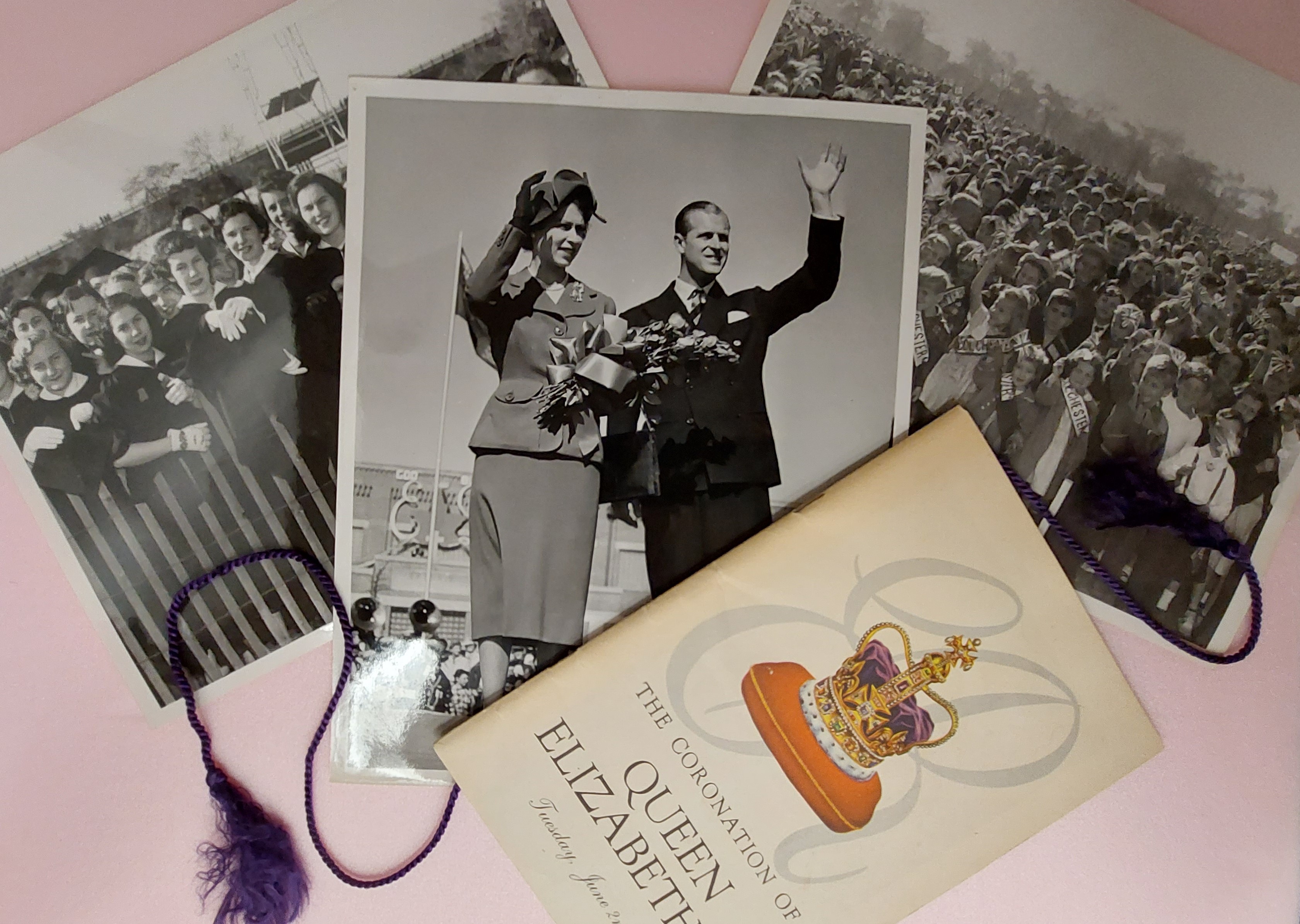

Here in the Leddy Library Archives & Special Collections we hold two files that offer glimpses into Elizabeth II’s life of public duty, and of her relationship with Canadians. The first file contains eighteen black and white photographs depicting Princess Elizabeth and her husband Prince Philip (1921-2021) on an October 1951 visit to Assumption College (which became the University of Windsor in 1964). Elizabeth was 25 years old and a mother of two: Prince Charles, age 2, and Princess Anne, age 1, remained in Britain during their parents’ first royal tour of Canada. The tour lasted just over a month and took them from coast to coast. Contemporaries observed that the visit was the “most-covered news event in Canadian history,” with some 4,500 media personnel accredited to cover the visit and millions of Canadians eager to see the royal couple. [1] The glamour and celebrity which would later attach itself to Diana Spencer, Kate Middleton, and Meghan Markle found an earlier precedent in Canadians’ intense excitement about the beautiful young wife and mother who would one day be their queen. That day came sooner than expected, with the death of King George VI only three months after the end of Elizabeth and Philip’s Canadian tour.

These 1951 photographs tell us a surprising amount about the future Queen’s brief time at Assumption College. First, they depict a royal couple dressed sensibly but with a certain flair: Prince Philip looks dashing in a dark suit, while Princess Elizabeth’s plain skirt-suit and low-heeled shoes are augmented with a floral brooch, a pearl necklace, a smart handbag, and a stylish hat. Their expressions are relaxed and cheerful, and they look disposed to be pleased with everything around them. This was in spite of the tour’s gruelling nature. Pierre Berton recounts that over 33 days Elizabeth met 53 mayors, inspected 24 guards of honour, accepted official bouquets from 23 little girls (one of whom is depicted in these photos), and shook hands at the rate of 30,000 times per day. After the tour concluded, the princess described Canada as “a land full of hope, of happiness, and of fine, loyal, generous-hearted people” – a place and a people she and her husband had come to love. [2]

The event was held in Assumption Park, a large grassy area filling what is now the portion of campus southeast of Assumption Hall and northwest of Wyandotte Street. The stone tower of Dillon Hall can be seen in the background to the right of the stage, and one of the Ambassador Bridge towers to the left. The Royal Standard, the Union Jack, and the Canadian Red Ensign flew on three flagpoles behind the stage, and a large display was attached to the brick wall of an adjacent university building (subsequently torn down): the ornate letters “E” and “P” (for Elizabeth and Philip) appeared on either side of a large maple leaf surmounted by a stylized crown, with the words “God Bless” above the whole. A uniformed brass band and an honour guard of Boy Scouts and RCMP officers in dress uniform stood just behind the stage, and the small number of men and women on stage were dressed formally for the occasion: three-piece suits for the gentlemen, and dresses, gloves, and hats for the ladies.

Two of the photos provide a bird’s-eye view of the event: thousands of people of all ages filled the park, lining security fences and surrounding the stage on all sides. One image depicts Boy Scout troop leaders and Basilian Fathers (the Catholic priests who ran Assumption College) clasping hands in a human chain, to hold back the pre-teen boys and girls pressing forward behind them, craning their necks to try to see past the adults. Other photos depict orderly rows of elementary school children, mostly white, sitting or standing at the edge of a roped-off area, waving small Union Jacks and grinning happily. Some came from rural areas of Essex County for the occasion: sashes and signs for Colchester and Mersea are visible. Another photo shows a large group of white female scholars (perhaps in their late teens or early twenties) in black academic robes, white gloves, and mortarboard hats. The expressions on the faces of all these spectators, as well as their sheer numbers, make it clear that this close encounter with Princess Elizabeth was a very big deal. [3]

The archives’ other Elizabeth II file contains a commemorative booklet produced by Gooderham & Worts distillery in honour of her 1953 coronation. As the first-ever televised coronation of a British monarch, this event brought royal pomp and circumstance into the homes of anyone with a television. The full-colour commemorative booklet now at the archives would have augmented the black and white television spectacle. Featuring portraits of the Queen and Prince Consort, and images and explanations of significant ceremonial objects including the Swords of State, the Royal Coach, the Coronation Chair, and Westminster Abbey, the booklet also includes a fold-out map of the Queen’s coach route through London and, on the reverse, the seating arrangement inside the church. The back inside cover presents a chart showing Elizabeth II at the end of a long list of British monarchs stretching back to Elizabeth I (1558-1603).

The entire coronation booklet implies both a presumed public hunger for details and insights into the symbolism of the occasion, as well as a desire to convey notions of tradition and stability through this ritualized contract between a queen and her people. Calling the coronation “a magnificent pageant patterned by tradition for over 900 years,” the booklet also emphasizes the relevance of these rituals – and of the Crown itself – in a modern age. The coronation “holds vast promise today for the fulfillment of the democratic ideal,” it states, through “a lovely young Queen, dedicating her life to uphold the right and to oppose oppression.” [4] (The Anglo-Canadian, monarchist authors of the booklet would not have considered Britain's vast territorial empire a form of oppression, and, in fact, probably would have viewed it with pride as a form of benevolent uplift.)

As the world bids farewell to Elizabeth II, these archival glimpses back to the very beginning of her career as monarch remind us that there is a reason so many Canadians find themselves saddened by her death. Despite the vast ocean between her home country and ours, the relationship of duty, service, and love between generations of Canadians and Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II – deliberately cultivated by royal visits and promotional publications like the ones discussed here – was surprisingly strong.

___________________________________________________________________

[1] “Princess Elizabeth’s 1951 Royal Visit to Canada,” CBC News, 30 June 2011 (updated 12 March 2012), https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/princess-elizabeth-s-1951-royal-visit-to-canada-1.1061794.

[2] “Princess Elizabeth’s 1951 Royal Visit to Canada,” CBC News, 30 June 2011 (updated 12 March 2012), https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/princess-elizabeth-s-1951-royal-visit-to-canada-1.1061794.

[3] The 1951 visit photographs can be found in: University of Windsor, Leddy Library Archives & Special Collections, Acc. No. 2014-007, Box 9, File 179. They were taken by various press photographers, and later acquired by the university’s Public Affairs office.

[4] The coronation booklet can be found in: University of Windsor, Leddy Library Archives & Special Collections, F 0004, Series IV, file 1.

___________________________________________________________________

Dr. Sarah Glassford is the Archivist in the Leddy Library Archives & Special Collections unit, and a social historian of 20th c. Canada.

Posted September 9, 2022

For anyone born over the past 70 years, Queen Elizabeth II (1926-2022) has been a rare point of stability in a fast-changing world. Her death on September 8th could not be called shocking (given her age and the gentle warning given to the public earlier in the day that she was under medical care), but for many people it nonetheless feels jarring. Whether you are a monarchist or republican, a royal-watcher or unconcerned with royal affairs, the death of Elizabeth II – Queen of Canada, Britain, and other nations of the Commonwealth since 1952 – marks the end of an era.

Here in the Leddy Library Archives & Special Collections we hold two files that offer glimpses into Elizabeth II’s life of public duty, and of her relationship with Canadians. The first file contains eighteen black and white photographs depicting Princess Elizabeth and her husband Prince Philip (1921-2021) on an October 1951 visit to Assumption College (which became the University of Windsor in 1964). Elizabeth was 25 years old and a mother of two: Prince Charles, age 2, and Princess Anne, age 1, remained in Britain during their parents’ first royal tour of Canada. The tour lasted just over a month and took them from coast to coast. Contemporaries observed that the visit was the “most-covered news event in Canadian history,” with some 4,500 media personnel accredited to cover the visit and millions of Canadians eager to see the royal couple. [1] The glamour and celebrity which would later attach itself to Diana Spencer, Kate Middleton, and Meghan Markle found an earlier precedent in Canadians’ intense excitement about the beautiful young wife and mother who would one day be their queen. That day came sooner than expected, with the death of King George VI only three months after the end of Elizabeth and Philip’s Canadian tour.

These 1951 photographs tell us a surprising amount about the future Queen’s brief time at Assumption College. First, they depict a royal couple dressed sensibly but with a certain flair: Prince Philip looks dashing in a dark suit, while Princess Elizabeth’s plain skirt-suit and low-heeled shoes are augmented with a floral brooch, a pearl necklace, a smart handbag, and a stylish hat. Their expressions are relaxed and cheerful, and they look disposed to be pleased with everything around them. This was in spite of the tour’s gruelling nature. Pierre Berton recounts that over 33 days Elizabeth met 53 mayors, inspected 24 guards of honour, accepted official bouquets from 23 little girls (one of whom is depicted in these photos), and shook hands at the rate of 30,000 times per day. After the tour concluded, the princess described Canada as “a land full of hope, of happiness, and of fine, loyal, generous-hearted people” – a place and a people she and her husband had come to love. [2]

The event was held in Assumption Park, a large grassy area filling what is now the portion of campus southeast of Assumption Hall and northwest of Wyandotte Street. The stone tower of Dillon Hall can be seen in the background to the right of the stage, and one of the Ambassador Bridge towers to the left. The Royal Standard, the Union Jack, and the Canadian Red Ensign flew on three flagpoles behind the stage, and a large display was attached to the brick wall of an adjacent university building (subsequently torn down): the ornate letters “E” and “P” (for Elizabeth and Philip) appeared on either side of a large maple leaf surmounted by a stylized crown, with the words “God Bless” above the whole. A uniformed brass band and an honour guard of Boy Scouts and RCMP officers in dress uniform stood just behind the stage, and the small number of men and women on stage were dressed formally for the occasion: three-piece suits for the gentlemen, and dresses, gloves, and hats for the ladies.

Two of the photos provide a bird’s-eye view of the event: thousands of people of all ages filled the park, lining security fences and surrounding the stage on all sides. One image depicts Boy Scout troop leaders and Basilian Fathers (the Catholic priests who ran Assumption College) clasping hands in a human chain, to hold back the pre-teen boys and girls pressing forward behind them, craning their necks to try to see past the adults. Other photos depict orderly rows of elementary school children, mostly white, sitting or standing at the edge of a roped-off area, waving small Union Jacks and grinning happily. Some came from rural areas of Essex County for the occasion: sashes and signs for Colchester and Mersea are visible. Another photo shows a large group of white female scholars (perhaps in their late teens or early twenties) in black academic robes, white gloves, and mortarboard hats. The expressions on the faces of all these spectators, as well as their sheer numbers, make it clear that this close encounter with Princess Elizabeth was a very big deal. [3]

The archives’ other Elizabeth II file contains a commemorative booklet produced by Gooderham & Worts distillery in honour of her 1953 coronation. As the first-ever televised coronation of a British monarch, this event brought royal pomp and circumstance into the homes of anyone with a television. The full-colour commemorative booklet now at the archives would have augmented the black and white television spectacle. Featuring portraits of the Queen and Prince Consort, and images and explanations of significant ceremonial objects including the Swords of State, the Royal Coach, the Coronation Chair, and Westminster Abbey, the booklet also includes a fold-out map of the Queen’s coach route through London and, on the reverse, the seating arrangement inside the church. The back inside cover presents a chart showing Elizabeth II at the end of a long list of British monarchs stretching back to Elizabeth I (1558-1603).

The entire coronation booklet implies both a presumed public hunger for details and insights into the symbolism of the occasion, as well as a desire to convey notions of tradition and stability through this ritualized contract between a queen and her people. Calling the coronation “a magnificent pageant patterned by tradition for over 900 years,” the booklet also emphasizes the relevance of these rituals – and of the Crown itself – in a modern age. The coronation “holds vast promise today for the fulfillment of the democratic ideal,” it states, through “a lovely young Queen, dedicating her life to uphold the right and to oppose oppression.” [4] (The Anglo-Canadian, monarchist authors of the booklet would not have considered Britain's vast territorial empire a form of oppression, and, in fact, probably would have viewed it with pride as a form of benevolent uplift.)

As the world bids farewell to Elizabeth II, these archival glimpses back to the very beginning of her career as monarch remind us that there is a reason so many Canadians find themselves saddened by her death. Despite the vast ocean between her home country and ours, the relationship of duty, service, and love between generations of Canadians and Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II – deliberately cultivated by royal visits and promotional publications like the ones discussed here – was surprisingly strong.

___________________________________________________________________

[1] “Princess Elizabeth’s 1951 Royal Visit to Canada,” CBC News, 30 June 2011 (updated 12 March 2012), https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/princess-elizabeth-s-1951-royal-visit-to-canada-1.1061794.

[2] “Princess Elizabeth’s 1951 Royal Visit to Canada,” CBC News, 30 June 2011 (updated 12 March 2012), https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/princess-elizabeth-s-1951-royal-visit-to-canada-1.1061794.

[3] The 1951 visit photographs can be found in: University of Windsor, Leddy Library Archives & Special Collections, Acc. No. 2014-007, Box 9, File 179. They were taken by various press photographers, and later acquired by the university’s Public Affairs office.

[4] The coronation booklet can be found in: University of Windsor, Leddy Library Archives & Special Collections, F 0004, Series IV, file 1.

___________________________________________________________________

Dr. Sarah Glassford is the Archivist in the Leddy Library Archives & Special Collections unit, and a social historian of 20th c. Canada.

Connect with your library